Why We Forgot Them: Lise Olsen on Memory, Media, and Marginalized Victims

Author Lise Olsen discusses her investigative book, The Scientist and the Serial Killer during a literary event at Book People in Austin, Texas.

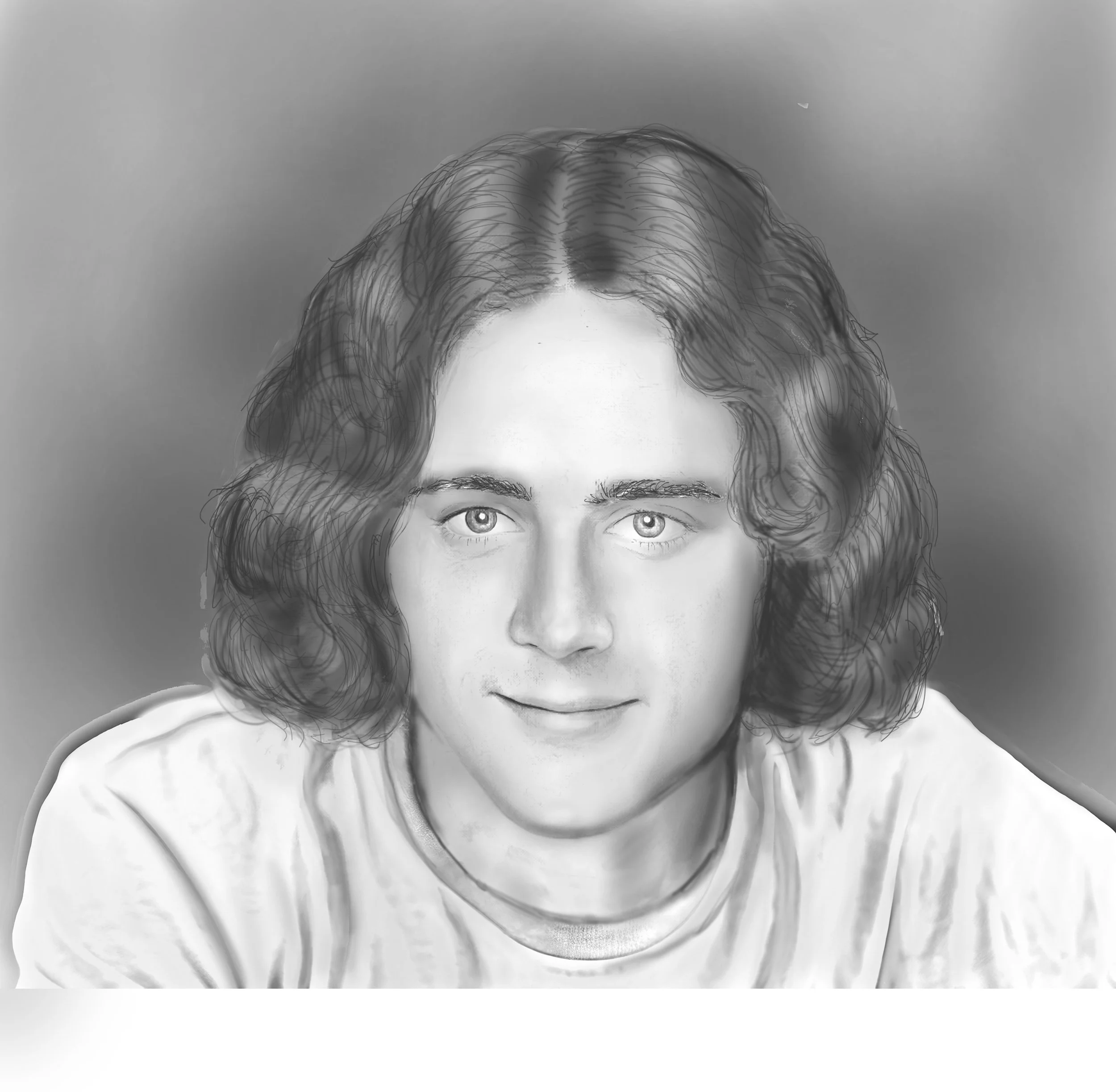

Mark Scott, 17, disappeared in 1973. His bones were later recovered and identified through work done by Dr. Sharon Derrick and her colleagues at Harris Co IFS, along with DNA evidence analyzed by the University of North Texas. The portrait was done by Nancy Rose.

Bones, lost souls, and remembrance: these are the threads that stitch together Lise Olsen’s chilling and compassionate exploration of justice in her latest novel based on true events, The Scientist and the Serial Killer: The Search for Houston’s Lost Boys.

Lise Olsen, investigative reporter and editor at The Texas Observer, crafts stories that ring truth and illuminate forgotten cold cases. Her latest book is based on the work of Texas forensic anthropologist Sharon Derrick. This story traces her relentless quest to uncover the identities of the victims of 1970s Houston-area serial killer Dean Corll, known as the Lost Boys. Derrick quickly became a voice for the forgotten and gives their stories the dignity they were once denied.

Olsen says the driving force behind this story is her belief that journalists, like herself, have the power to make a meaningful impact, particularly when their work brings hidden or overlooked facts to light. All the while, new methods including genetic genealogy and other genetic databases help bridge these missing identities.

Forensic Anthropologist Sharon Derrick works with a yellow robotic arm in a lab, using bubble wrap to test its grip near a model skull and set of teeth in her lab in Corpus Christi.

“I think that by writing about cold cases, by writing about the unidentified, by looking for cases that, perhaps you know are newsworthy, there's evidence that was left at the death scene, that might be something someone would recognize,” Olsen said.

The Scientist and the Serial Killer centers on Dr. Sharon Derrick as she works to uncover the identities of Dean Corll’s victims, at least 27 and possibly more teenage boys and young men murdered in Houston between 1970 and 1973. Known as the “Candy Man,” Corll, aided by two teenage accomplices, lured victims with promises of parties or rides, then restrained, tortured, and killed them, often by strangulation or gunshot.

Delving into her book, The Scientist and the Serial Killer, Olsen reflects on the nature of media coverage during one of Houston's darkest chapters and the long-overlooked victims known as the Lost Boys.

“There was lots and lots of media coverage at the time that Dean Corll was killed by his accomplice in August 1973 but up until then, there was very little coverage of all these disappearances,” Olsen shared. “Some of these parents put up flyers everywhere, did whatever they could, and there wasn't much coverage of missing kids, and they were presumed to be runaways.”

Cop at Chopped Car and Shovels Uncovering are from Corll's boatshed in August 1973.

After Dean Corll was killed by his teenage accomplice in August 1973, the discovery of at least 27 bodies triggered a media frenzy, even attracting international coverage. Under intense public scrutiny, local authorities rushed to make arrests, quickly detaining two teens linked to the case while the search for victims was still ongoing. Despite journalists probing Corll’s background, many leads were ignored, and deeper questions, like the identities of eight unnamed victims, went largely unexplored. Families who had reported their children missing received little attention, and the overwhelming scale of the horror seemed to paralyze efforts to investigate further. In the chaos, many voices were left unheard.

Roy “Ikie” Bunton, 19, was never reported missing. His bones were later recovered and identified through work done by Dr. Sharon Derrick and her colleagues at Harris Co IFS, along with DNA evidence analyzed by the University of North Texas. The portrait was done by Nancy Rose.

“There weren't a lot of interviews with other families whose kids were missing. You know, some of these kids who were eventually identified. Their families reported them missing right away, and if someone had really been digging into it at the time, they might have been able to help these families,” Olsen said. “And in 1973 I think journals were sort of overwhelmed by the quantity of murder victims and the amount of horror that the experience was causing in the community, but there weren't a lot of efforts to interview.”

One of the most disturbing aspects of the Dean Corll case was how little attention was paid to the fact that 11 victims had been photographed by a porn ring. Despite the gravity of this revelation, media coverage was minimal, reflecting the era’s limited legal protections for minors and a lack of public awareness around sex crimes. At the time, concepts like sex trafficking weren’t widely understood, and police departments had yet to establish specialized child sex crime units. The infrastructure to investigate and respond to such abuse simply didn’t exist.

Randell Lee Harvey, 15, disappeared March 1971. His bones were later recovered and identified through work done by Dr. Sharon Derrick and her colleagues at Harris Co IFS, along with DNA evidence analyzed by the University of North Texas. The portrait was done by Nancy Rose.

While many journalists tried their best to cover the Dean Corll case, class bias still seeped into the narrative. One prominent book from the 1970s, though considered well-written, portrayed a victim’s working-class family in a mocking tone, highlighting how media depictions often reflected societal judgments.

“I think that there were at least two victims of color and one, two more victims who had some Native American blood. I think class was more the issue in terms of the police response,” Olsen said. “You know, they just sort of dismissed these kids as runaways, and that was the bigger issue. But I think certainly the ethnicities had some role."

Donnie Falcon, 17, disappeared July 1, 1971. His bones were later recovered and identified through work done by Dr. Sharon Derrick and her colleagues at Harris Co IFS, along with DNA evidence analyzed by the University of North Texas. The portrait was done by Nancy Rose.

Among the victims of Dean Corll were two known Hispanic boys. One family, which had Native American ancestry, received some attention in media coverage and books. But the other Hispanic victim remained unidentified for years, and his family was largely overlooked, possibly by choice, though the reasons are unclear. Decades later, journalist Skip Hollandsworth revisited the case in a 2011 article and interviewed the surviving parents. The father, who has since passed away, even wrote a personal memoir to honor his son’s memory.

These disparities in attention, where some families were heard and others overlooked, invite a deeper conflict with how collective memory functions, shaping which victims are mourned publicly and which are quietly forgotten.

“I think that at the time certainly some people whose families were intact, who had the resources to hire to take their kids to a dentist, ended up having their kids identified first, those were white families and one Hispanic family with some means,” Olsen said. “The kids whose families didn't have that, or there was just a mom at home, and they weren't being listened to as much by the police. Those kids tended to get forgotten because of resources. And I think that's still true today.”

Joseph Allen Lyles, 17, disappeared in Febuary 1973. His bones were later recovered and identified through work done by Dr. Sharon Derrick and her colleagues at Harris Co IFS, along with DNA evidence analyzed by the University of North Texas. The portrait was done by Nancy Rose.

While the specifics of the case belong to another era, the dynamics it reveals, whose stories get prioritized and whose are left in silence, still echo today, especially in how missing persons from marginalized communities are treated.

“There just aren't enough resources. There's been a lot of defunding of the police, and I understand, the protests that have happened, but you know, part of the part of what happens is that the cold case units get cut first, or they don't get created at all, and the kinds of forensic science resources that are needed to help solve cold cases, often involve collaboration with DNA labs or collaboration with genetic genealogists, and not every county, even in Texas, for example,” Olsen said. “Even has a medical examiner's office where there are either pathologists or forensic scientists of any kind.”

Steven Ferdig-Sickman, 17, disappeared in July 1972. His bones were later recovered and identified through work done by Dr. Sharon Derrick and her colleagues at Harris Co IFS, along with DNA evidence analyzed by the University of North Texas. The portrait was done by Nancy Rose.

Resources for forensic investigations can vary drastically depending on location, some rural areas or states may lack access to specialists like forensic scientists or anthropologists, especially in cases involving identification. Cold cases often receive the least attention due to public forgetfulness, making journalistic coverage crucial in keeping these stories alive.

Beyond the logistics of identification and justice, what lingered in Derrick was something deeper, a quiet reckoning with the emotional weight of telling the stories of boys who had been buried not just physically, but within the folds of forgotten history.

“The secondary, of course, the people who lost these people, these brothers, friends, children, they suffer much more than I did, but to hear them talk about it and have the responsibility of trying to bring back to life these young men whose lives were cut short was something that was at times, very emotionally difficult,” Olsen confessed.

Olsen said there were stretches of time when she needed to step away from the work.

Michael Baulch, 15, disappeared in July 1973. His bones were later recovered and identified through work done by Dr. Sharon Derrick and her colleagues at Harris Co IFS, along with DNA evidence analyzed by the University of North Texas. The portrait was done by Nancy Rose.

“I thought in my mind that it's important for other people, the readers, to know about these kinds of cases and about how important these identifications are to families. About how when identifications are not made, sometimes criminals get away with their crimes and continue to do them,” Olsen said.

Willard K. “Rusty” Branch Jr. , 18, disappeared in 1972. His bones were later recovered and identified through work done by Dr. Sharon Derrick and her colleagues at Harris Co IFS, along with DNA evidence analyzed by the University of North Texas. The portrait was done by Nancy Rose.

Olsen became involved in a project covering missing and unidentified persons, after co-authoring a series tied to the Green River Killer case.While researching, she and her colleague compiled the first public list of unidentified people in the state, eventually spotlighting a mother and child whose identities had long gone unknown. Publishing a portrait of the child helped police make a breakthrough. Years later, Olsen was contacted by the woman’s brother, who recognized the portrait and confirmed the identities through DNA. This experience deeply affected her, demonstrating how journalism can meaningfully impact forgotten cases and grieving families.

She reflected that these stories, especially those overlooked by institutions, carry a vital role in surfacing justice and humanity. Olsen now sees her reporting as a way to preserve the memory of the Lost Boys through the pages of her book, through Sharron Derrick's commitment to justice, and through the hearts of those who loved them.